Upon first glance at the laid-back Des Moines, Iowa area, many people would consider it an ordinary mid-sized midwestern city with just over 200,000 people. Des Moines is gradually investing in revitalizing its downtown and drawing in new residents with its low cost of living. However, even with revitalization and investment, Des Moines’ communities of color continue to suffer from the effects of discriminatory housing policies.

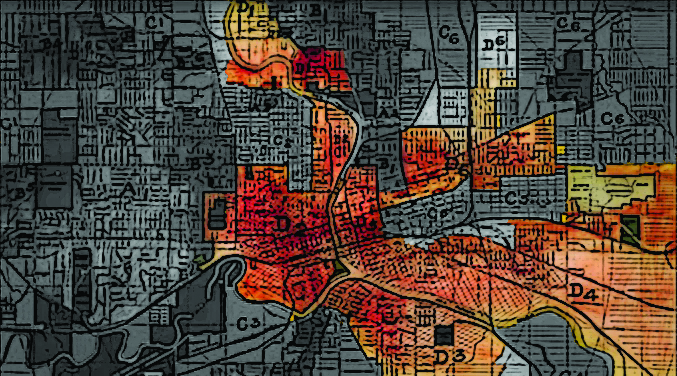

Dr. Jane Rongerude, an expert in Community and Regional Planning at Iowa State University, described redlining as “the practice of putting a line on a map that was red and saying, no, no mortgage lending here.”

Like in most American cities, discriminatory housing practices began in Des Moines following the Great Depression with the creation of the city’s first redlined maps in the mid 1930s by the Home Owners Loan Corporation.

In an attempt to quickly reinvigorate the economy, the government started offering low-cost mortgages to homeowners in an effort to stop the growing rise in foreclosures. However, many well-qualified minority applicants, especially Black individuals, were denied loans because of their race and where they looked to live. “This [redlining] is a deeply entrenched part of our system that was really created to prevent African American households and other households of color [from home ownership], although really, was focused on and remained the longest and continues to for African American households,” Dr. Rongerude said.

As a consequence of the Federal Housing Authority labeling minorities as high risk investments in their 1938 lending policies and manual, redlined areas received little to no investment from banks and mortgage lenders. This created a cycle of disinvestment in redlined areas, with the people of color being unable to obtain loans for housing repairs and home purchases. Although redlining was outlawed with the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968, its effects are still felt today.

Abena Imhotep, a Des Moines native, TEDx speaker and most recently— student, discussed growing up off 13th St. and Mondamin Ave, a previously redlined area. “My childhood home is zoned by the city’s Planning and Zoning Commission [as] residential only. Which sounds great, unless you want to open a business,” Imhotep said. “There’s no opportunity for economic drivers, and so that keeps people marginalized, and it’s policies like that, that perpetuate marginalization.”

One notable Black community that prospered in Des Moines despite redlining was Center Street. Center Street would frequently flood, making it an unstable area to live in. Black Iowans were frequently given mortgage lending near Center Street due to it being a flood-prone area. Center Street emerged as a jazz hotspot, featuring an array of jazz clubs and numerous Black-owned businesses: including the first Beauty School in Iowa, according to University of Iowa Archives and Iowa City based Little Village Magazine.

“My parents migrated as part of, I think it was probably at the tail end of the great migration, from New Albany, Mississippi to Des Moines,” Imhotep recalled. “They had heard about Center Street and they thought, ‘Okay, so there’s a bustling area that is all Black that you can thrive,’ And so they got here, and Center Street was gone.”

Center Street thrived until the 1960s when urban renewal programs began, along with the construction of interstate highways, specifically Interstate235 in Des Moines. Black communities were often bulldozed to build these highways, while white neighborhoods were left unscathed.

Because of the effects of redlining and urban renewal, Black Americans and other minorities in the Des Moines area continue to struggle to own their own homes and grow their wealth. Decades of divestment into previously redlined areas have made it hard for communities of color to catch up. “If you can’t get a mortgage to buy your home, if you can’t get a mortgage to improve your home. Even if you can scrap together cash or find other lending sources your neighborhood [is] going to remain low-income because people aren’t going to be able to generate wealth,” Dr. Rongerude said.

Today, Black Iowans continue to face discrimination when it comes to home loans. From 2014 to 2017, Black individuals were denied home loans at a rate of about 24% , compared to Polk County’s overall denial rate of around 11% per One Economy.

In Des Moines, only 33% of Black Iowans own their own home, compared to 73% of white Iowans, according to the National Equity Atlas. Imhotep is ready to own her own home, she’s happily married and her kids are grown up. Yet, she continues to face barriers to homeownership. “I’ve even looked personally at ways to get homeownership because I live in a really nice house that I don’t own,” Imhotep said.

Imhotep explained how the Des Moines area has changed aesthetically and noted the community is “inundated” with Non-profit organizations that might be hurting more than helping. “The perimeter of the entire community is nonprofit organizations, most of whom have a mission of alleviating suffering poverty; lifting people out of their economic circumstance or other things,” Imhotep said. “But it’s a cycle of keeping people in and I’m like, ‘what in the world is going on?’ I don’t know if anybody is really being lifted up.”

This lack of integration has major implications on the growth of neighborhoods. Predominantly white neighborhoods in the Des Moines metro area have higher incomes and better housing stability than predominantly minority communities. Areas like Johnston—where the median 2020 household income is around $93,000, and about 80% of residents are white, have seen better economic growth than more integrated neighborhoods. “You have these areas that are white, and they stay white. And I think that’s really the question, ‘What can we do to break up that problem?”’ Dr. Rongerude said.

Imhotep mentioned how she lived next to Chautauqua Park, a community that was originally all-white and had restrictions against Black individuals buying homes in that area.

“So you had a green line community nestled in the middle of a red line community. They had restrictive covenants, but it was literally on the other side of some shrubs,” Imhotep said. Okay, so there’s that, but I think the long term impacts of redlining are redlining. It’s the grandchild of redlining.”

In Des Moines, white neighborhoods not only have higher incomes but less poverty and lower incarceration rates. One Economy reported, “The median household income for Black or African American households in Polk County is $33,816. In comparison, the median household income for all of Polk County is $63,530.”

Imhotep expressed a feeling of hopelessness and internalized oppression she’s felt within the community when it comes to the topics of hunger, poverty, and oppression. “We’ve got all these amazing construction projects and innovation[s] happening. But you see [the] struggle getting worse for a lot of people and it’s the the diversity of who’s in trouble, is shocking to me.”

In addition to being behind in income and homeownership, Black Iowans are also behind in renting. According to One Economy’s 2020 Action report, 69.3% of Black Iowans rent their homes, compared to 32.9% of the general population. Additionally, “53.3 percent of African Americans are cost-burdened renters in the Des Moines-West Des Moines metro area. Renters are considered cost-burdened if they pay more than 30% of their income towards rent.”

“Anything that promotes housing stability, I think is the solution. Anything that promotes community building so that neighbors can support each other,” Dr. Rongerdue said. “Right, because eviction and displacement, it affects the whole community, as well as just continued work on fair lending practices, homeownership opportunities, things like that.”

One organization, the Polk County Housing Trust Fund, is pushing to increase Black homeownership in Des Moines and close the housing gap by implementing national housing programs and a more cohesive guide of resources for Black homeowners.

“So nationally, there is an effort called 3 by 30, which is trying to create 3 million Black homeowners, new Black homeowners by 2030. You know, that requires a partnership among people who do mortgage lending, realtors, others in the world of housing supports to help make that possible and communities,” Matt Hague, the Trust Fund’s Communication Director said. “So we’re trying to find the ingredients of success and bring them here.”

There is no quick fix to dismantle the effects of discriminatory housing practices. However, incremental changes and housing initiatives are proving to be promising for the Des Moines metro area. Rental homeownership assistance programs are helping bridge the gap.

In April, the PCHTF received $15 million in aid from the Federal Government’s 2021 American Rescue Plan Act. A proportion of these funds will go toward building multi-family housing “with an emphasis on supportive housing for underserved populations,” according to Polk County’s Recovery Project Performance Review.

Community organizations such as IMPACT: Community Action Partnership offers emergency rental assistance programs and tenant based rental programs. They are contracted with Polk County to administer housing funds from the American Rescue Plan Act. Anne Bacon, IMPACT’S CEO explained how they’ve seen an increase in the usage of their programs. “Typically assisting people with housing, we’d serve about 185 families. In the last year and a half, we’ve served 10,000,” Bacon said. “So it was a real ramp up, but even prior to the pandemic funding, we had a homeless prevention program and tenant based rental assistance program.”

Local banks and lending institutions have also created programs to help people secure housing loans. One such lending organization is the Neighborhood Finance Corporation which offers home improvement and first-time homeowner loans. “It’s almost like meeting people’s needs so that we can all focus on the bigger picture and, I think for the city of Des Moines, that’s something that the city loses sight of.” Imhotep said.